- Economy Insights

- Posts

- The Great Depression Explained

The Great Depression Explained

What It Was and Why It Happened

The Great Depression (1929–1939)

The Great Depression was the longest and deepest global economic downturn of the modern era. It began in the United States in 1929 and lasted about a decade. During this time industrial output and prices collapsed, unemployment soared, and poverty spread worldwide. For example, between 1929 and 1933 U.S. industrial production fell nearly 47%, GDP fell 30%, and one-quarter of workers were jobless. The onset is usually dated to the stock market crash of October 1929, which wiped out massive fortunes and shattered confidence. From that point onward, a series of economic crises and policy failures turned a recession into a global depression.

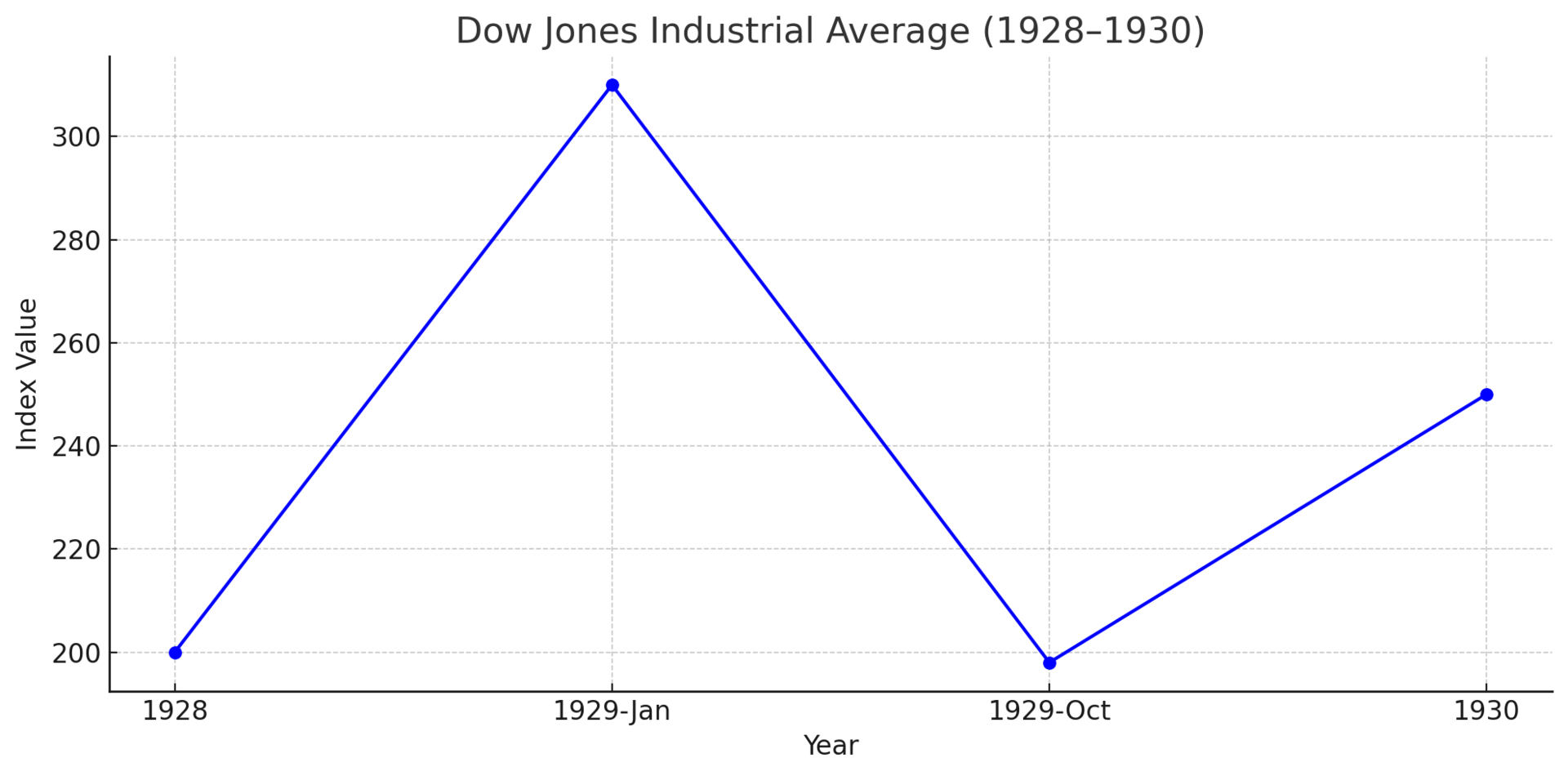

This chart illustrates the dramatic decline in the U.S. stock market during the onset of the Great Depression. After years of speculative growth, stock prices peaked in 1929 but plummeted in October during “Black Thursday” and “Black Tuesday,” marking the start of the financial collapse.

Causes of the Great Depression

Historians agree there was no single cause; rather, a “perfect storm” of factors combined to trigger the crash and deep slump. Key factors included:

Stock Market Speculation and Crash: In the late 1920s, U.S. stock prices rose to unprecedented levels as investors bought on margin (borrowing to invest). When prices began to fall in October 1929, panic selling accelerated the decline. The crash destroyed wealth and confidence, curtailing consumer spending and investment.

Bank Failures and Monetary Contraction: From 1930–1933 the U.S. suffered four waves of bank runs and failures. Nearly one-third of banks failed by 1933. Without deposit insurance or central-bank support, each wave of panic brought more banks down, shrinking the money supply. The Fed’s mistakes – such as raising interest rates in 1928–29 to curb speculation – inadvertently triggered recessions in Europe as well. By hoarding cash, people further reduced credit and spending.

Gold Standard and Global Spillover: Most countries (including the U.S., Britain, and France) tied their currencies to gold. When the U.S. economy collapsed, gold flowed into the U.S., forcing other countries to deflate to maintain their gold parity. Facing gold losses, many foreign central banks raised interest rates, deepening recessions abroad. In short, the gold standard transmitted and magnified the downturn internationally.

Trade Collapse and Tariffs: World trade fell sharply. The U.S. enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930), imposing heavy duties on imports. This provoked retaliatory tariffs and sparked a global trade war. By some estimates, international trade fell by over 50%, starving export-dependent economies like Germany and Latin America of markets. Decreased lending from American banks (as interest rates rose) also helped tip other economies into crisis.

Underlying Imbalances and Overproduction: In the late 1920s many industries and farms were already producing at capacity, and consumer demand was financed by debt. When demand faltered, overproduction led to price collapses (especially in farming) and higher debt burdens. These hidden weaknesses made any shock much worse.

In short, excessive debt and speculation combined with policy errors (bank runs, deflationary central banks, and trade barriers) to produce a self-reinforcing downturn.

Timeline of Events (1929–1939)

1929 (Oct): Stock Market Crash. After nearly a decade of boom, stock prices collapsed. On October 24 (“Black Thursday”) and October 29 (“Black Tuesday”) 1929, frantic selling drove the market into a free fall. This crash destroyed wealth and shook confidence.

1930: Tariffs and Panics. In June President Hoover signed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, raising U.S. import duties to record levels. Foreign retaliation followed. By the fall of 1930, the first of four major U.S. banking panics began: depositors rushed to withdraw funds, leading to multiple regional bank failures.

1931: Worsening Worldwide. Banking panics spread in spring and fall 1931. Global trade and prices fell. Notably, Britain abandoned the gold standard in September 1931, devaluing the pound to stimulate recovery (an action that helped its economy recover sooner). In Germany and elsewhere, U.S. loan withdrawals triggered sharp contractions.

1932: Election of FDR. By 1932 the U.S. was in full-blown depression. Over 25% of American workers were unemployed, and thousands of banks had closed. In November, voters swept Herbert Hoover out of office. Franklin D. Roosevelt won a landslide victory on promises of vigorous federal action.

1933: Bank Holiday and New Deal Begin. On March 6, 1933, FDR declared a national “bank holiday,” closing all U.S. banks and inspecting them for solvency. Sound banks reopened; insolvent ones remained closed. Over the next months Roosevelt launched his First Hundred Days: a flurry of legislation creating agencies and programs. Among these were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) – all intended to provide jobs, stabilize prices, and rebuild infrastructure. Financial reforms created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to prevent bank runs and stock fraud.

1933–1935: Recovery Begins (Gradually). These New Deal measures and a partly loosening money supply helped the economy to stabilize and grow somewhat. Unemployment and output improved from their nadir, though they remained far below 1929 levels. In agriculture, the Dust Bowl drought intensified rural hardship even as programs began paying farmers to cut production.

1937–1938: Double-Dip Recession. In 1937 the U.S. economy slipped back into recession as Roosevelt cut spending and raised taxes. Industrial production and employment fell again. This showed the recovery was still fragile.

1939 and beyond: World War II Mobilization. The Great Depression effectively ended as the U.S. (and other nations) ramped up production for World War II. By the early 1940s, factory output and jobs rebounded fully (for example, U.S. industrial production returned to 1929 levels by 1942). Internationally, Germany, Japan, and others also recovered industrially by the mid-1930s, although France lagged until late in the decade.

Government and Policy Responses

As the crisis deepened, governments experimented with many policies:

Hoover’s Approach (1929–1933): President Herbert Hoover initially relied on voluntary business cooperation and state-level relief. He resisted direct welfare aid to individuals, believing it would weaken morale. In 1930 he did sign the Smoot–Hawley tariff (to help U.S. farmers), but that worsened global trade. In 1931 Hoover finally backed creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to make loans to banks and railroads. However, these measures were seen as too little, too late. Homeless camps mockingly dubbed “Hoovervilles” sprang up, blaming the president for the hardship.

Roosevelt’s New Deal (1933–1939): FDR campaigned on bold federal action. In his first inauguration (March 1933) he famously declared that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” instilling hope. His administration enacted sweeping New Deal reforms. Early laws addressed banking (Emergency Banking Act, Glass-Steagall banking reform) and created jobs programs. A succession of agencies (CCC, WPA, TVA, NRA, etc.) put millions to work and regulated industry. Landmark legislation like the Social Security Act of 1935 provided old-age pensions and unemployment insurance. These programs expanded the role of the federal government in ways that endure today. (For instance, the FDIC and SEC still exist, and Social Security still provides retirement income.) Roosevelt also pushed labor laws (Wagner Act) and farm subsidies to stabilize prices.

International Actions: Many governments took corrective steps too. As mentioned, Britain left gold in 1931 and recovered more quickly. Other nations created work projects and social safety nets. Ultimately, only massive WWII spending ended the slump for good: factories building ships, tanks, and planes finally put people back to work.

“First of all,” FDR said at his 1933 inauguration, “let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” This bold rhetoric marked a new resolve to use government power against the Depression. Conversely, as early as 1931 Hoover had optimistically claimed that “prosperity was just around the corner,” a stance many Americans came to view as tragically out-of-touch.

The Great Depression brought widespread hardship and reshaped societies:

United States: Unemployment soared to unprecedented levels. By 1933 roughly 25% of the U.S. labor force was jobless (straining one-quarter of households), and many more under-employed. Poverty and homelessness surged: soup kitchens and bread lines became common in cities. Rural areas also suffered: the Midwest and Great Plains endured the Dust Bowl drought and windstorms, displacing farming families. Marriage and birth rates fell, and migration patterns shifted (for example, Dust Bowl “Okies” moved to California). The crisis also undermined faith in classical economic ideas, setting the stage for a new belief in social welfare and regulation.

Political Shifts in the U.S.: The Depression shattered the old Republican dominance. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition united urban working people, farmers, African Americans, and others in support of Democrats. At the same time, debates raged over the limits of government: Supreme Court battles (e.g. on business regulation), Roosevelt’s 1937 “court-packing” plan, and labor strikes (e.g. auto workers) highlighted rising class tensions.

Global Effects: The Depression was truly worldwide. By 1932 global GDP was down 15%, similar to the U.S. contraction. Industrial centers in Britain, France, Germany, and Japan all saw major declines. International trade fell about 60% from 1929 to 1932. Countries coping by slashing spending and even embracing dictatorships. For example, Weimar Germany was hit hard by the loss of U.S. loans and trade; by 1933 about 30% of German workers were unemployed, a factor that helped fuel the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party. In many nations, economic hardship led to political extremism or sweeping reforms. Authoritarian regimes emerged in Italy, Germany, Japan and elsewhere, often justified as solutions to economic chaos. In contrast, democracies like Britain and the U.S. eventually responded with social reforms.

Social Toll: Everywhere, ordinary people endured fear and uncertainty. Homeless encampments, “Hoovervilles,” appeared in many cities (named after Hoover’s perceived failure). Children went hungry and schools closed. Yet popular culture (novels, movies, radio) reflected both despair and hope. In the U.S., incidents like the Bonus Army protest (1932) showed veterans marching for relief. Internationally, family budgets shrank as unemployment rose (e.g. by 1933 about 20% of Americans were jobless).

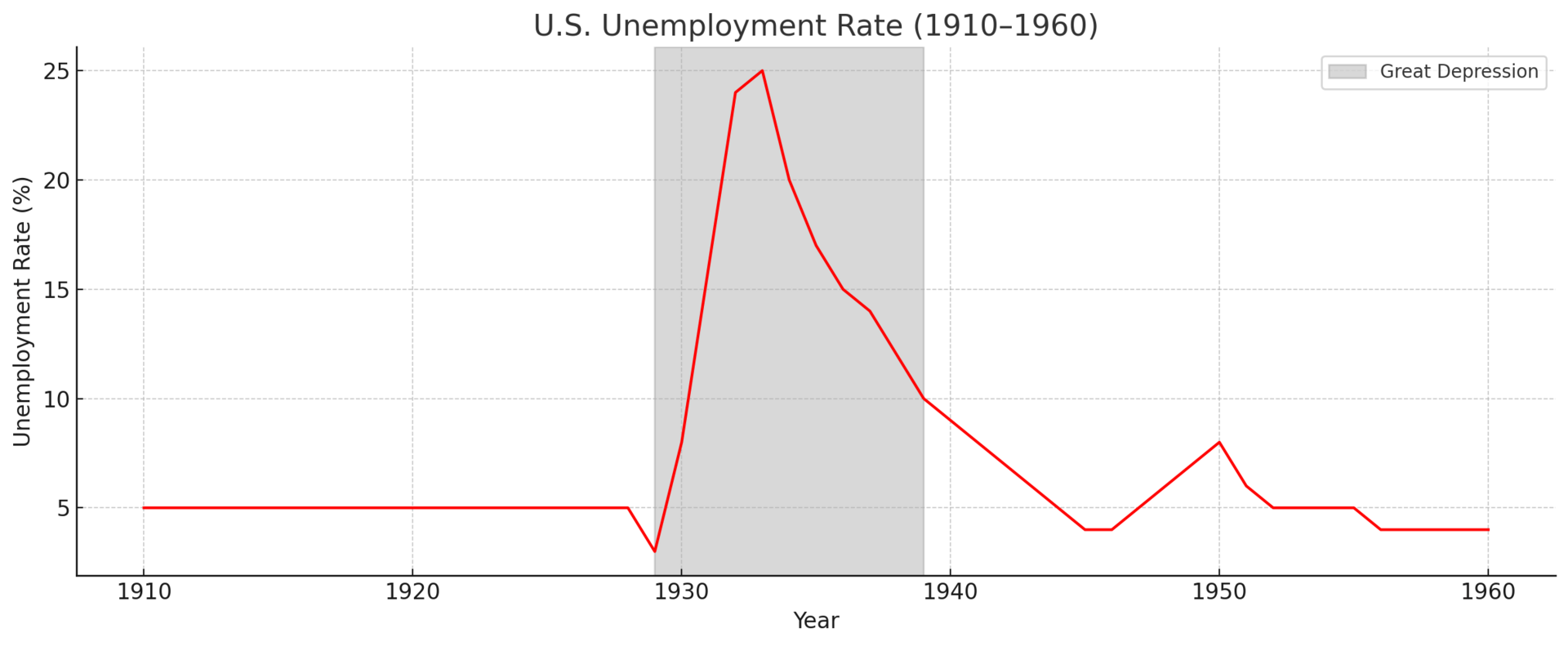

This chart shows unemployment rates over five decades, with a sharp spike between 1929 and 1933 during the Great Depression. Unemployment soared from around 3% to over 20%, reflecting the devastating impact on American workers. The shaded area highlights the Depression years.

Key Figures

Herbert Hoover (U.S. President, 1929–1933): A Republican engineer-turned-president, Hoover inherited the crash and favored voluntarism over direct aid. He believed in balancing budgets and relying on charities. He signed high tariffs (Smoot–Hawley) and created the RFC for banks, but refused to fund large-scale relief programs. As the crisis worsened, Hoover lost public support – he told Americans (early in 1930) that “prosperity was just around the corner,” a prediction that came to seem hopelessly optimistic. He was defeated in 1932, leaving office with unemployment at record highs.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (U.S. President, 1933–1945): The Democratic winner of 1932, FDR broke with Hoover’s laissez-faire approach. A charismatic leader, he launched the New Deal and dramatically expanded the federal government’s role. Roosevelt introduced Social Security, labor rights, and major public-works programs that created jobs. He famously reassured Americans in 1933 that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” as he vowed bold action. FDR also pushed for financial reforms: Glass-Steagall banking laws, the FDIC (insured deposits), and the SEC (regulating stocks) were meant to prevent past abuses. His leadership during 1933–41 fundamentally changed U.S. governance and helped restore confidence, though full recovery required the WWII effort.

John Maynard Keynes (British Economist): Though not a politician, Keynes was a towering influence on Depression-era thought. He argued that when private demand collapsed, only public spending could restore full employment. His work ("The General Theory," 1936) argued against austerity during slumps. Keynes’s bold view – summed up by his quip “In the long run, we are all dead” – held that governments should act immediately to boost demand, not wait for markets to fix themselves. These ideas were novel in the 1930s and would shape post-war economic policy (Keynes even helped design the Bretton Woods system in 1944). His advocacy helped legitimize deficits and public investment as tools to fight depression.

Recovery Efforts: New Deal and International Responses

Recovery was uneven and controversial. In the U.S., the New Deal programs (1933–1939) provided some relief and reform but did not fully end the slump. For example:

Job Creation Programs: Agencies like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed millions on public works – building roads, parks, schools and more. The TVA electrified the rural Tennessee Valley. These put a floor under employment.

Farm and Labor Policies: The Agricultural Adjustment Act paid farmers to reduce surpluses, raising crop prices. The National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act, 1935) guaranteed collective bargaining. By 1937 nearly 8 million Americans had joined labor unions.

Social Safety Nets: The 1935 Social Security Act created retirement pensions, unemployment insurance, and welfare for dependents. These programs provided long-term assistance to the needy (and still exist today).

Financial Regulation: The Glass-Steagall Act (1933) separated commercial banking from investment banking and created the FDIC to insure deposits. The SEC (1934) monitored the stock market. These reforms aimed to prevent the reckless behavior that had caused earlier crashes.

Despite these efforts, a rebound in 1937-38 showed the economy remained fragile. It was ultimately wartime spending (building ships, planes, weapons) that fully restored demand and employment. Internationally, leaders took lessons from the Depression: many countries abandoned gold and stabilized their currencies. Austerity measures were often abandoned. In the long run, the shock prompted global changes in economic policy.

Lasting Impacts on Economic Policy

The Great Depression left a permanent mark on financial systems and policymaking worldwide:

Keynesian Economics: Before the 1930s, governments rarely ran deficits. Keynesian ideas of counter-cyclical fiscal policy (spend in slumps, save in booms) gained traction. After WWII, most industrialized nations adopted active demand-management, inspired by Keynes’s work.

Social Safety Nets: Governments built welfare states to protect against future crashes. The U.S. Social Security and unemployment insurance systems, unemployment benefits in Europe, and labor protections all trace back to 1930s reforms.

Financial Regulation: Stricter financial safeguards became the norm. Bank deposit insurance (FDIC) and stock-market oversight (SEC) established in the 1930s remain cornerstones of stability. Glass-Steagall (though partially repealed in 1999) set the precedent for limiting risky bank activities.

Global Financial Architecture: The Depression showed the dangers of uncoordinated national policies. At the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, Roosevelt and Keynes helped create the IMF and World Bank, aiming to maintain currency stability and provide reconstruction aid. The era ushered in fixed exchange rates (pegged to the dollar/gold) and multilateral cooperation to prevent another collapse.

Regulatory Philosophy: Faith in unfettered markets was shaken. Most governments accepted a larger role in managing the economy. Economic theory also evolved: unemployment was no longer seen as a natural adjustment process but as a problem requiring policy intervention.

In short, policymakers learned that unchecked economic cycles could have devastating social costs. Modern central banks, welfare programs, and international financial institutions all trace their roots to lessons of the 1930s. The Great Depression’s legacy is a more proactive, government-involved approach to preventing and mitigating economic crises.

Social, Political, and Economic Consequences