- Economy Insights

- Posts

- Sovereign Credit Ratings

Sovereign Credit Ratings

How Agencies Assess Country Risk

Sovereign credit ratings are independent evaluations of a government’s creditworthiness. They help investors gauge the risk of lending to a country and influence the interest rate a country must pay. In general, a higher rating (e.g. AAA) signals low risk and cheaper borrowing, while a low rating (e.g. B or C) warns of high risk and expensive debt. Governments often seek ratings from Moody’s, S&P Global Ratings, and Fitch – the three largest agencies – in order to attract investment and access international bond markets. A good rating is usually essential for emerging economies that want low-cost financing.

Key Factors in Sovereign Ratings

Rating agencies analyze a broad set of quantitative and qualitative factors. While methodologies differ somewhat, they all examine similar country attributes:

Economic Strength and Growth: Agencies look at GDP size and growth trends, per-capita income, economic diversity and productivity. For example, robust growth and a large economy (measured by GDP) make a country more resilient to shocks. Moody’s assigns an Economic Strength score based on long-term growth trends and economic size, and S&P explicitly considers “Economic structure and growth prospects” in its model.

Fiscal Policy and Debt Burden: The government’s budget balance and debt load are critical. Analysts check metrics like the debt-to-GDP ratio, budget deficit, interest payments as a share of revenue, and contingent liabilities. High debt or persistent deficits can signal trouble. Fitch’s criteria, for example, use indicators such as government debt/GDP, interest-to-revenue and fiscal balance to measure fiscal health. S&P’s Fiscal factor likewise assesses debt sustainability and budget flexibility.

Monetary Policy and Inflation: Stability in prices and exchange rates matters. Low, stable inflation and credible central bank policies strengthen a rating. If inflation is high or a country lacks control over its currency, that raises risk. For instance, Fitch explicitly scores real GDP growth volatility and inflation under its macroeconomic pillar. S&P includes “Monetary flexibility” as a factor, reflecting how easily the central bank can combat inflation and support growth.

External Position (Foreign Liabilities): A country’s balance-of-payments and foreign reserves are checked to see if it can handle external shocks. Indicators include current account balance, foreign exchange reserves, external debt, and net international investment position. For example, Fitch’s model weights net foreign assets/GDP, import cover by reserves, and current account plus FDI inflows. These gauges show how vulnerable a country is to currency or debt crises. S&P’s External liquidity factor similarly looks at reserve adequacy and external financing flexibility.

Political and Institutional Factors: Analysts evaluate government effectiveness, stability, and policy predictability. Strong institutions (rule of law, low corruption, sound governance) bolster confidence. Fitch explicitly lists “political stability and capacity” and governance indicators among its structural factors. S&P’s methodology has an Institutional factor for government effectiveness and rule-of-law issues. Moody’s also includes an Institutions and Governance factor. Political turmoil or weak institutions (for example, repeated policy reversals or conflict) can lead to downgrades.

Together, these factors – often broken into sub-categories – form the basis of the agencies’ analysis. In practice, sovereign rating committees use a mix of quantitative scoring and expert judgment to arrive at a final rating.

Rating Agencies’ Methodologies

The major agencies each publish detailed criteria that explain how they translate these factors into a letter-grade rating. Generally, they all use structured frameworks and scorecards, then allow for committee judgment:

Fitch Ratings: Fitch employs a Sovereign Rating Model (SRM) with four analytical pillars: structural features, public finances, external finances, and macro performance/policies. Each pillar has specific indicators. For example, under Public Finances, Fitch looks at government debt/GDP, interest-to-revenue, fiscal balance/GDP and the share of foreign-currency debt. Under External Finances, it examines FX reserves, net foreign assets, current account plus FDI, etc.. These quantitative inputs generate an “SRM score” which corresponds to a preliminary rating range (e.g. AAA to B–). The sovereign rating committee can then apply a qualitative overlay of up to a few notches to capture additional considerations (such as political shocks) not fully captured by the numbers. In crises, Fitch may even extend its usual adjustment range beyond ±3 notches to account for rapidly changing conditions. Notably, if a country falls below CCC+, Fitch relies more on its rating definitions (C, RD) rather than the SRM.

S&P Global Ratings: S&P’s framework centers on five key rating factors: Institutional effectiveness, Economic structure and growth prospects, External liquidity and international investment position, Fiscal flexibility and performance, and Monetary flexibility. Each factor is assessed on a 1–6 scale (1=strongest, 6=weakest), using both hard data and qualitative judgment. S&P then combines these scores into two profiles: an “institutional and economic profile” (the average of the Institutional and Economic scores) and a “flexibility and performance profile” (the average of External, Fiscal, and Monetary scores). Those profiles map to an indicative rating. Finally, the sovereign rating committee may notch the rating up or down to reflect unique risks or strengths not fully captured (such as policy changes or structural shifts). This process yields S&P’s published rating (e.g. AAA, AA, A, etc.) along with an “Outlook” (Positive/Stable/Negative) indicating future trend.

Moody’s Investors Service: Moody’s uses a scorecard approach that integrates an Economic Resiliency score with a Fiscal Strength score, plus an adjustment for Susceptibility to Event Risk. First, Moody’s grades a country’s Economic Strength and Institutions and Governance Strength. These two factor scores are combined equally to form an Economic Resiliency outcome. Separately, a Fiscal Strength score is calculated based on debt dynamics, fiscal balance and financing flexibility. Moody’s then blends Economic Resiliency and Fiscal Strength (using dynamic weights that depend on debt level) to produce a Government Financial Strength score. Finally, analysts consider Susceptibility to Event Risk – which explicitly accounts for political volatility, government liquidity risk, banking sector stress, and external shocks – that may lower the scorecard-indicated outcome. A country with very high political or external risk may see its score reduced. The result is a final government rating (e.g. Aa2, Ba1, Caa3) with an outlook. Moody’s committees can also override or adjust the scorecard result through judgment, but they publish this framework to show the key drivers of each rating.

Each agency publishes periodic updates to its methodology (for example, Fitch revised its criteria in April 2023). The bottom line is that all three agencies combine economic data (GDP, debt levels, reserves, etc.) with qualitative analysis (policy credibility, governance, crisis management ability) to judge sovereign credit risk. They stress that past default history, the consistency of policies, and even the quality of a country’s official statistics can influence the assessment.

Impact on Borrowing Costs and Markets

Sovereign ratings have real-world financial consequences. A higher rating (especially in investment-grade territory) generally translates into lower borrowing costs. When a country’s rating is raised, investors view its bonds as safer, so yields can fall. Conversely, a downgrade typically pushes yields up. Research and market experience show this effect is most pronounced for emerging markets. For example, a UN analysis found that a negative rating action (such as a downgrade or negative outlook) tends to increase an emerging market’s borrowing spreads by about 160 basis points, compared to roughly 100 basis points for an advanced economy. This is partly because many institutional investors (pension funds, banks) rely on ratings to set investment rules or capital charges.

A particularly sharp effect comes when a country falls from investment-grade (e.g. BBB–) into speculative-grade (junk). Funds that are restricted to investment-grade assets may be forced to sell, causing a “cliff effect” that floods the market and drives yields even higher. In practice, a rating downgrade signals to all investors that the country’s debt is riskier, which raises the sovereign’s risk premium. That in turn can slow capital inflows and even trigger capital outflows if investors rebalance away.

Rating agencies are aware of this power. They often note that their downgrades come after bond yields have already widened, but for many small or emerging economies the agency signal can accelerate changes in market confidence. In contrast, raising a rating – or placing it on positive watch – can bolster investor confidence. For example, Moody’s in July 2025 cited progress on Argentina’s reforms and an IMF program when it upgraded Argentina’s rating by two notches, noting these developments “reduce the likelihood of a credit event”. That action helped improve Argentina’s access to funding at better rates.

Ratings also affect a country’s access to capital markets. Some investors have mandates to hold only bonds above a certain rating. If a sovereign slides too low, it may effectively lose a portion of its investor base. This can force governments to turn to official lenders (IMF, World Bank) or pay much higher rates to compensate risk. Thus, governments closely watch their ratings – even sometimes requesting agencies to delay a downgrade or reviewing methodology changes – because ratings influence the yield curve on their debt.

Recent Case Studies

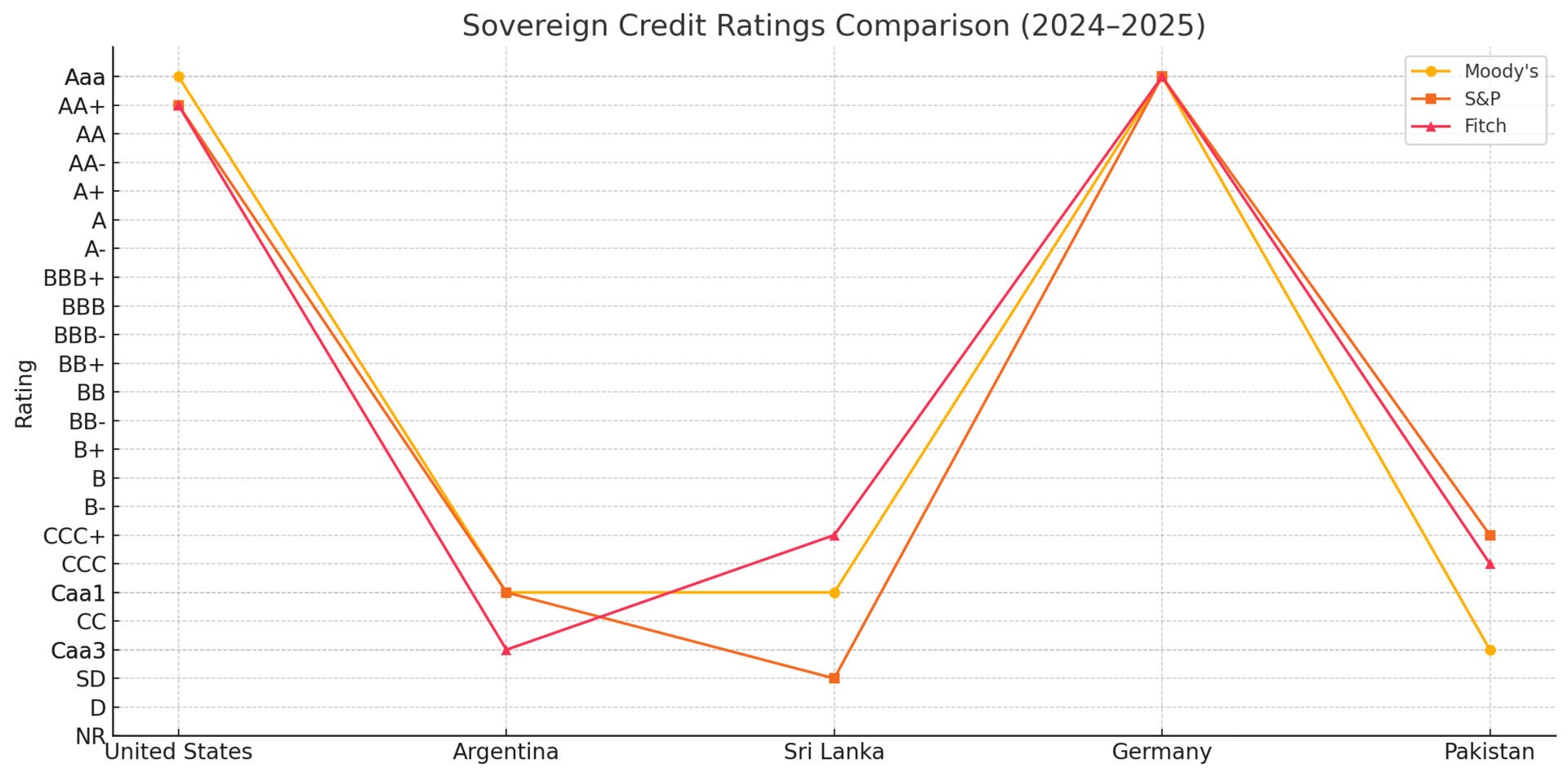

Argentina. After years of macro instability and defaults, Argentina’s credit ratings have fluctuated dramatically. In early 2023, Fitch Ratings cut Argentina’s foreign-currency rating to C (the lowest level above default), warning that a government-mandated bond swap by state entities essentially amounted to a default in progress. Fitch stated “a default is imminent” given this debt conversion and said it would place the rating in default once the swap occurs. At that time, Moody’s had Argentina at Caa3 (also non-investment grade) with a stable outlook, and S&P’s rating was two notches higher. (Later, in mid-2025, Moody’s raised Argentina to Caa1 after the new government eased currency controls and secured an IMF deal.) These moves show how agencies respond to concrete policy actions: Fitch saw the forced debt exchange as highly credit-negative, while Moody’s was somewhat more optimistic about Argentina’s reforms and external support.

Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s brutal economic crisis led to sovereign default in April 2022. The country’s foreign debt rating plunged into “Restricted Default” (RD) territory. However, after Sri Lanka restructured roughly $12.5 billion of debt and reduced its foreign liabilities, both Moody’s and Fitch reversed course in late 2024. On December 23, 2024, Moody’s upgraded Sri Lanka’s long-term rating to Caa1 from Ca (stable outlook), noting that the debt overhaul “reduces external vulnerability and government liquidity risk” and improves prospects for fiscal sustainability. In the same period, Fitch lifted Sri Lanka’s rating to CCC+ from RD once international bondholders approved the swap. These changes illustrate that substantive policy actions and financial aid (IMF support) can improve a sovereign rating, even after a default.

United States. The U.S. has traditionally been one of the world’s highest-rated sovereigns, but political brinkmanship over debt limits has drawn scrutiny. In August 2023, Fitch downgraded the U.S. long-term rating one notch to AA+ from AAA, joining S&P (which had cut the U.S. in 2011) in taking the U.S. off the top rung. Fitch cited “fiscal deterioration” over the coming years and, notably, repeated last-minute debt-ceiling fights as eroding confidence in governance. Fitch’s report explicitly warned that decades of political deadlock on fiscal policy had weakened the country’s credit strength. The U.S. Treasury and White House called the downgrade “arbitrary” and based on outdated data, highlighting one controversy of ratings in action. In markets, U.S. yields barely moved on the day, reflecting belief in the U.S. economy, but the downgrade did dent the nation’s reputation for fiscal discipline. (As this example shows, major advanced economies rarely lose rating points, and any change attracts intense media coverage.)

Other countries have also made headlines. For example, Pakistan saw upgrades in 2024 as it met IMF targets, and many European countries’ ratings were cut during the eurozone debt crisis a decade ago. In each case, agencies pointed to specific factors: rising debt ratios, inflation, or policy weaknesses for downgrades, and debt relief deals or strong export performance for upgrades.

Sovereign Credit Ratings Comparison (2024–2025)

This chart compares sovereign credit ratings from Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch for five countries. The lower the position, the stronger the rating. While the U.S. and Germany hold top-tier ratings, Argentina, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan remain in speculative territory, with some signs of recovery after defaults and restructuring.

Criticisms and Controversies

The sovereign rating process is not above reproach. Critics have identified several issues:

Potential Bias: Sovereign ratings rely more on analyst judgment than corporate ratings do, since political willingness to pay and governance are subjective factors. Some observers argue agencies may favor advanced economies. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, advanced economies saw much larger output losses than developing ones, yet accounted for only about 5% of total sovereign downgrades. This raised suspicions of bias: why were emerging markets hit with more downgrades despite faring relatively better economically? (It could reflect risk aversion toward poorer countries, or simply that EMs had more debt in the first place.) Whatever the cause, the perception of unfair treatment can undermine confidence in rating accuracy.

Cliff Effects and Procyclicality: Ratings tend to fall during downturns and rise in booms, which can exacerbate market swings. A downgrade to junk (non-investment grade) can trigger massive capital outflows — a “cliff effect” that accelerates crises. Likewise, agency upgrades during booms (when fundamentals already look strong) can give a green light that fuels excess borrowing. Studies have documented this cyclical pattern, especially among emerging markets. Thus some say ratings amplify volatility rather than smooth it.

Timing and Information Lag: Agencies use historical data and long-term averages, which can make ratings slow to reflect turning points. Critics often note that governments can behave badly until a crisis is imminent (when ratings are finally cut). For example, U.S. officials complained in 2023 that Fitch’s downgrade was based on “outdated data” even after the debt ceiling was resolved. In fairness, agencies argue that they take a conservative, forward-looking view, but the use of annual figures means ratings sometimes trail market sentiment or real-time events.

Conflict of Interest (Issuer Pays): Sovereign issuers (governments) pay agencies for their ratings, creating a potential conflict. Unlike a model where investors pay for opinions, the “issuer-pays” system could, in theory, bias ratings upward. This issue is well-known from the corporate bond market, but it applies at the country level as well. Nations have little choice but to seek ratings, so agencies face a structural incentive to maintain good relationships with sovereign clients. (Some experts have argued that this could lead to more favorable ratings than if the agencies were paid by an independent source.)

Lack of Transparency: The detailed models and deliberations of rating committees are not fully public. While agencies publish criteria outlines, the exact weightings and qualitative judgments are opaque. This can frustrate governments and investors who want to understand why a rating changed. The subjectivity in sovereign rating also means two agencies can differ: for example, Fitch rated Argentina two notches lower than Moody’s in early 2023. Such discrepancies fuel debate over methodology.

In addition, some critics note that sovereign ratings may underweight long-term risks like climate vulnerability or structural inequality, since the standard horizon is only a few years. The UN has highlighted that agencies are beginning to integrate environmental and social risks, but this is still an evolving area.

Despite these criticisms, sovereign ratings remain central to global finance. Regulators and law require or favor them in many contexts, so changing their role is difficult. Agencies themselves acknowledge past missteps (for example, they tightened criteria after the 2008 financial crisis). Over the years, regulators in the U.S. and EU have also promoted more competition and transparency among the big three.

Conclusion

Sovereign credit ratings boil down a complex reality into a single letter grade, but that mask of simplicity rests on deep analysis. Agencies carefully study a country’s economy, finances, policies, and institutions to form a holistic risk picture. These assessments – grounded in the data points above – then influence global capital flows: they affect interest rates on sovereign bonds, the cost of borrowing for businesses, and the overall investor confidence in a country. While ratings can shift only gradually (to avoid abrupt market shocks), they serve as important benchmarks.

In summary, Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch evaluate sovereign credit risk using broadly similar frameworks: they look at economic output and stability, fiscal balances, monetary policy, external debt and reserves, and political/institutional strength. Each agency combines quantitative scorecards with expert judgment to assign a rating that reflects the probability of default and repayment ability. Case studies from around the world – Argentina’s turmoil, Sri Lanka’s default and recovery, even the U.S. debt-ceiling standoff – illustrate how real-world events map into rating actions. Finally, ratings are not beyond critique: observers point to biases, delayed reaction, and systemic effects. Nevertheless, they remain a key tool for investors and policymakers to gauge country risk.

Sources: Authoritative rating agency criteria and financial analysis, including Fitch’s and S&P’s published methodologies, Moody’s sovereign rating framework, and recent news and studies on sovereign ratings. These cover factors, methods, and case examples relevant to sovereign risk assessment.