- Economy Insights

- Posts

- F-35 Price Tag

F-35 Price Tag

How Much Does One Jet Really Cost?

The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II program is often cited as the most expensive weapons system in history. This fifth-generation stealth fighter comes in three variants – the F-35A (conventional takeoff and landing), F-35B (short takeoff/vertical landing, STOVL), and F-35C (carrier variant for CATOBAR operations) – each with different capabilities and costs. Beyond the sticker price of a new jet, the F-35 incurs substantial lifecycle costs for operations, maintenance, and upgrades over decades. Below, we break down the unit costs of each variant with recent figures, explain why they differ, examine the long-term sustainment expenses, review how unit prices have changed over time, and discuss what U.S. allies are paying for their F-35s (including any premiums or discounts in international sales).

Unit Cost of F-35A, F-35B, and F-35C Variants

Per-Jet Unit Cost (Flyaway): The “flyaway” cost – essentially the procurement cost for one additional aircraft, including its engine – varies by variant. Recent data from the F-35 Joint Program Office shows:

F-35A (Air Force CTOL version) – roughly $80–83 million per jet in the latest production lots. This is the cheapest variant.

F-35B (Marine Corps STOVL version) – about $109 million per jet. The lift-fan and swiveling nozzle for vertical landing make it more complex and expensive.

F-35C (Navy carrier variant) – around $102 million per jet. It has larger folding wings and reinforced landing gear/tailhook for carrier ops, costing slightly more than the A but less than the B.

These figures are average flyaway costs for production Lots 15–17 (delivered in 2023–2025). They represent a typical unit without extras. The F-35A is the lowest-cost because it is the simplest design and is produced in the largest quantity. The F-35B is the priciest due to its unique vertical lift system and lower production volume, while the F-35C falls in between. Table 1 summarizes current unit costs and also includes illustrative international prices:

F-35 Variant | Latest U.S. Unit Cost (Flyaway) | Example Allied Unit Cost (Package) |

|---|---|---|

F-35A (CTOL) | ~$82.5 million (Lot 15–17 average) | Japan: ~$128 million per jet (including engine and local assembly) |

F-35B (STOVL) | ~$109 million (latest lots) | U.K.: ~$115 million per jet (flyaway, 2020) |

F-35C (Carrier) | ~$102 million (latest lots) | N/A – no foreign operators of F-35C (U.S. only) |

Why the Price Differences? The F-35B’s cost is highest because of the engineering needed for short takeoff/vertical landing – it contains a Rolls-Royce lift fan system and swiveling exhaust, adding weight and complexity. The F-35C’s cost is elevated by its larger wings and structural enhancements for carrier landings. In contrast, the F-35A is a more conventional design produced at greater scale, yielding economies of scale and a lower per-unit price. All variants share many common parts, but those unique features drive the B and C variants to cost 20–30% more than the baseline A model. Another factor is production volume: the F-35A makes up the majority of the planned fleet (USAF and most foreign customers), so its unit price has benefitted most from the learning curve and bulk buys.

Flyaway vs. Fully Loaded Cost: It’s important to note that the flyaway prices above cover the jet ready to operate on the runway (airframe, engine, basic avionics). However, they do not include ancillary expenses like depot-level tools, support equipment, spare parts, initial training, or munitions. When those are added, the effective cost per aircraft is higher. One analysis pegs the “total package” unit cost (including spares, support, depot maintenance setup, etc.) at about $110.3M for an F-35A, $135.8M for an F-35B, and $117.3M for an F-35C. These figures illustrate that a significant investment in support infrastructure accompanies each jet. (For example, an F-35A’s weapon system unit cost including extras was over $110M vs. ~$82M flyaway.) Allies buying the F-35 often purchase comprehensive support packages, which is reflected in higher per-jet figures in those deals (discussed more under international pricing).

Lifecycle Costs: Operations, Maintenance, and Long-Term Support

Buying an F-35 is just the beginning – the operating and support (O&S) costs over its lifespan far exceed the purchase price. The F-35 is expected to serve into the 2070s, and sustaining the fleet is projected to cost trillions.

Total Program Sustainment: The U.S. Department of Defense’s latest estimates (2023 Selected Acquisition Report and GAO analysis) project roughly $1.6 trillion in O&S costs over the life of the program. This is up from about $1.1 trillion estimated in 2018, reflecting a 44% increase in projected sustainment expenses. The growth is partly due to the Pentagon extending the planned service life and recognizing higher actual operating costs. At ~$1.6 trillion, the F-35’s sustainment alone makes it “the most expensive weapons system in U.S. history.”

Cost Per Year and Per Hour: On a per-aircraft basis, the annual operating cost is very high. The U.S. Air Force reports it is spending about $6.6–$6.8 million per year, per F-35A to operate and sustain each jet. This covers fuel, maintenance (parts and labor), repairs, and upgrades. It equates to an hourly flight cost of roughly $33,000–$36,000, several times more than legacy fighters. (By comparison, older F-16s or F/A-18s were typically in the $20k per hour range or less.) The services originally hoped to get the F-35’s operating cost down to about $4 million per jet per year, but real-world figures are substantially higher – the Air Force’s ~$6.8M per plane/year is well above the $4.1M target set earlier. The Navy and Marine Corps have similarly found their F-35 variants more expensive to fly and maintain than anticipated. These higher sustainment costs have forced the services to adjust, for example by reducing planned flight hours per jet and increasing budgets, to keep the program affordable.

Lifecycle per Jet: If an F-35 operates for say 30 years, at ~$6–7M in annual O&S, its lifetime sustainment would be on the order of $180–$210 million (not accounting for inflation). Many jets may serve longer (the program intends to keep some airframes in service for up to 66 years from first deployment, through multiple refurbishments). Estimates for full life-cycle cost per aircraft vary, but are eye-opening. For instance, an analysis of Australia’s F-35A program suggested a single F-35A could cost around $475 million over its lifetime when including operating costs, compared to about $126 million just to acquire it. While methodologies differ, the clear takeaway is that sustainment costs are multiple times the purchase price.

Major drivers of these costs include the sophisticated maintenance needs of stealth technology (coatings, etc.), a global spare parts supply chain, engine overhauls, and the F-35’s advanced Autonomic Logistics Information System/ODIN maintenance software (which has faced development issues). The Pentagon and Lockheed Martin have ongoing efforts to reduce the cost per flight hour – Lockheed claims to have cut its portion of those costs by 50% since 2015 – but the F-35 will likely remain more expensive to operate than earlier fighters. Even so, the services consider the high cost worthwhile for the leap in capability, and are seeking efficiencies (like longer part lifespans, improved repair processes, and performance-based logistics contracts) to control sustainment expenses.

In sum, when budgeting for an F-35, one must plan not just for the ~$80–100M procurement, but also on the order of hundreds of millions in fuel, maintenance, upgrades, and support over decades of service. This reality underpins debates in Congress and allied nations about how many F-35s to buy, and how to balance F-35 procurement with funding for its upkeep.

Cost Trends Over Time: From Development to Today

The F-35’s price tag has not been static – it has evolved significantly from the early days of the program to the present, generally trending downward for unit costs (until recently) as production matured. Here’s a look at how the per-jet cost has changed:

Initial Estimates vs Reality: When the Joint Strike Fighter program began, the F-35 was marketed as a more affordable 5th-generation fighter. Early notional estimates around 2001 imagined a unit cost around $50 million per aircraft. These proved far too optimistic. By 2010, as development delays and overruns mounted, the Pentagon recognized unit costs had ballooned – initial projections of $50M had risen to $92M–$135M+ per jet according to DoD estimates at that time. In other words, the F-35 was already double or triple the advertised cost before it even entered service. This prompted cost-cutting initiatives in 2010–2012 to rein in the program.

Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP) Lots: The F-35 was procured in annual lots while still in development (concurrency), which meant early jets were very expensive. For example, LRIP Lot 6 (contracts in 2013) came in at about $100.8M for an F-35A, $108.5M for an F-35B, and $120M for an F-35C. Lot 7 (2014) saw modest reductions (A for $96.8M, B $104.2M, C $115.2M). These prices illustrate that in the early-mid 2010s, an F-35A still cost around $100 million and the other variants well above that – a far cry from the $50M figure once bandied about.

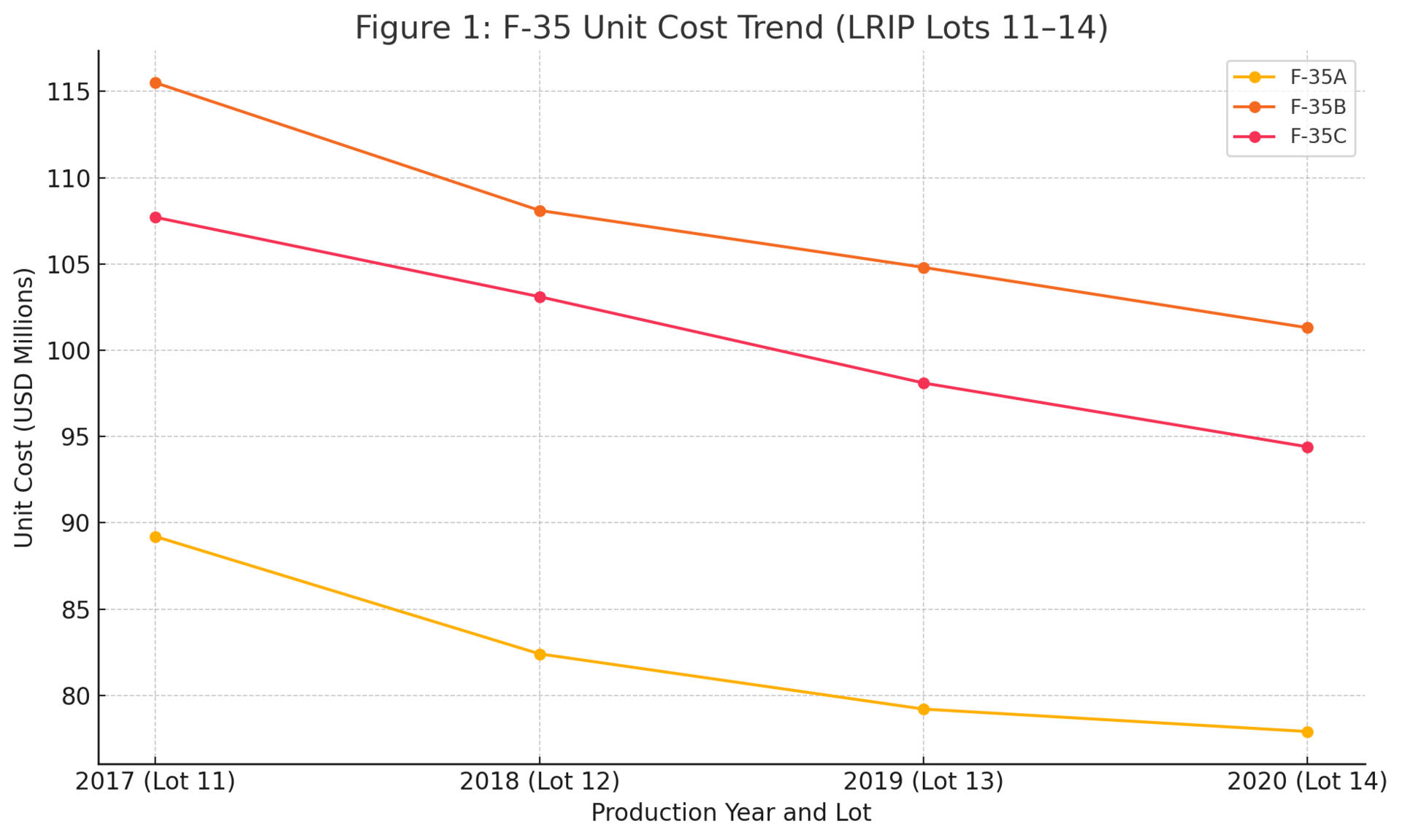

Economies of Scale and “Blueprint for Affordability”: As production ramped up in the later LRIP lots, unit costs started falling more steeply. The contractor and DoD implemented efficiency initiatives and negotiated bulk buys. From LRIP Lot 11 to Lot 14 (FY2017–FY2020), there was about a 12–13% drop in unit cost across the board. A major milestone was reached with the Lot 14 contract (signed 2019): the F-35A unit cost fell below $80 million for the first time. Specifically, Lot 14 prices were approximately $77.9M (F-35A), $101.3M (F-35B), and $94.4M (F-35C). This met the U.S. Air Force’s goal of an $80M F-35A one year ahead of schedule. For context, just two years prior in Lot 11, an F-35A was ~$89 million – so costs in those late LRIP lots fell rapidly due to larger orders and efficiencies. By 2020, the program was hailing that the F-35A cost was comparable to (or even less than) legacy jets like new F-15s, on a flyaway basis.

Current and Future Trends: In the early 2020s, the downward trend in unit price bottomed out and has slightly reversed or leveled due to factors like inflation, supply chain issues, and the end of big block-buy contracts. The latest Lot 15–17 agreement (2023) reflects small increases – e.g. the F-35A average is around $82.5M (in then-year dollars) for jets delivering 2023–25. The F-35B and C in those lots are ~$109M and ~$102M respectively, as noted earlier. External pressures (COVID-19 impacts, higher material costs, etc.) have made it challenging to keep reducing the price in the near term. However, the cost is still far lower than earlier years – roughly half of what an F-35A cost a decade ago. The program’s learning curve has largely been realized; further significant cost drops would likely need a major increase in production volume or new efficiency breakthroughs. In fact, the Joint Program Office warned that starting with Lot 15, unit prices could increase by a few percent due to these economic factors.

Overall, the F-35’s unit cost trajectory went from highly underestimated, to soaring over $100M for early jets, then gradually down to ~$80M, and now holding roughly steady (with slight upticks) around that level. Figure 1 below illustrates this trend from LRIP to full-rate production:

Figure 1: F-35 Unit Cost Trend. The negotiated unit prices for F-35A, B, and C from LRIP Lot 11 through Lot 14, showing the F-35A dropping to $77.9M by Lot 14. Early lots were higher (Lot 6 & 7 were ~$100M+ for F-35A). Recent lots (15–17) average around $82M (A), $109M (B), $102M (C).

(Note: “Flyaway” cost as used here includes the engine. It excludes broader program costs like R&D. The Average Procurement Unit Cost (APUC), which amortizes total procurement spending (including support items) over the fleet, is higher. For example, one official estimate put the F-35’s APUC at $132.7M per aircraft (in 2012 dollars) when dividing all procurement funds by 2,456 jets. But if anticipated foreign orders (~918 jets) are included, the effective average cost per jet would drop into the $62–77M range. This simply reflects spreading fixed costs over more units.)

Export and International Pricing

Many U.S. allies and partner nations are buying the F-35, but the price they pay per aircraft can vary based on partnership status, local assembly, and included support packages. Generally, all buyers benefit from the economies of the joint production program (there isn’t a separate “export version” price for the airframe itself), but foreign customers may face additional fees or costs. Here’s how it breaks down for key buyers:

Program Partners vs. FMS Customers: The F-35 was developed with 8 international partners (UK, Italy, Netherlands, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Turkey (now removed)) who contributed funding and expertise. These partners buy jets at the same base unit cost as the U.S. does, through the cooperative production program. Other nations purchase F-35s via the U.S. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) process (e.g. Japan, Israel, South Korea, Poland, etc.). FMS buyers typically pay a U.S. government administrative fee (~3.5–3.8%) on top of the contract cost, and they often opt for comprehensive support packages in their deals, which can make the headline cost per jet appear higher than the flyaway cost alone.

United Kingdom: The UK, a top-tier Level 1 partner, has so far only ordered the F-35B for its Royal Air Force/Royal Navy. As a partner, the UK shares in the production lot pricing. Recent statements put the flyaway cost of an F-35B around £85 million (approximately $100–115M) per jet in current dollars. Indeed, a UK Minister in 2020 cited $115 million as the unit cost of their F-35B (including engine) at that time – this was about 24% cheaper than the first UK jets, reflecting the downward trend. The UK’s contracts also involve British industry (BAE Systems builds ~15% of each F-35). There is no special discount per se for the UK, but being a partner means they were part of development and get some return in subcontracts. The UK’s most recent planned order (26 additional F-35Bs, announced 2022) was projected at ~£2.2 billion including support, which aligns with ~£85M per jet flyaway cost plus supporting elements. In summary, Britain pays roughly the same unit flyaway price as the U.S. for F-35Bs, but must budget for support, upgrades, and national-specific integrations (like UK weapons) on top.

Japan: Japan is an FMS customer (not an original partner) and is acquiring both F-35A and STOVL F-35B models. Japan’s approach illustrates how extras can drive up per-jet costs. Japan insisted on assembling many of its F-35As domestically at a Final Assembly and Check-Out (FACO) facility built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. This added infrastructure cost roughly $1 billion, which when amortized added an estimated $26M per jet for the first 38 aircraft. In a 2017 budget document, Japan’s MoD estimated the cost of six F-35As at ¥15.7 billion each (~$137M) including engines and local assembly. After negotiations to trim support costs, they reduced it to ¥14.6B (~$128M) per jet. That figure included the FMS fee and all support gear. Japan’s big 2019–2020 order of 105 F-35s (63 A’s and 42 B’s) was approved at an estimated $23 billion total. That package included not just the airframes but 110 engines, spares, logistics, training, and ongoing support. When you divide it out, it suggests over $200M per aircraft, but that is not the jet’s unit cost – it’s a reflection of the substantial support and training systems purchased along with the fighters. In reality, Japan’s base aircraft price is similar to U.S. costs (their F-35A flyaway was expected to drop below $100M by Lot 10–11), but their all-in program unit cost is higher due to local assembly expenses and FMS overhead. Japan effectively pays a premium for domestic assembly and self-sufficiency, but has negotiated savings on support where possible.

Israel: Israel was the first country to buy F-35s through FMS and calls its customized F-35A variant the “F-35I Adir.” The U.S. subsidizes much of Israel’s F-35 purchase through Foreign Military Financing (grant aid), but the nominal costs can be seen in recent deals. In 2023, Israel agreed to buy a third squadron of 25 F-35A jets for about $3 billion. That package “comes complete with support and maintenance services”. Simple math puts it at $120M per jet on average, which again reflects more than just the airframe (it includes spares, support equipment, and maintenance for a period of time). Earlier, Israel’s first 50 F-35I aircraft were reportedly purchased for roughly $100M apiece (flyaway), with deliveries between 2016 and 2024. Israel also has unique software and electronic modifications, which the U.S. approved and partly funds. Overall, Israel’s unit costs are in line with other customers (they benefit from the economies of the main production lots), but as an FMS buyer they pay the administrative fee and have invested in their own infrastructure (e.g. special depots) to maintain the jets. U.S. aid covers the bulk of these expenses. The recent $3B deal underlines that even for 25 additional jets, the support tail is significant – Israel is effectively pre-paying for sustainment in that cost.

Australia: Australia is a Level 2 partner in the program and is buying 72 F-35A fighters to replace its F/A-18 Hornets. Australia’s 2020–21 defense reports indicate the total acquisition program cost is about A$16–17 billion for 72 jets. In U.S. dollars, that was roughly $12B at the time, which averages to ~$160M per F-35A including all ancillaries. The Aussies have set up an F-35 support system in-country and will utilize the global supply network for parts. An Australian analysis (RAAF Air Power study) noted an average unit procurement cost around $125M (likely including some support) and a lifetime cost approaching $400–$500M per jet when through-life support is included. Like other partners, Australia pays basically the same unit flyaway price as the U.S. – in fact, Australian jets are bought in the same production lots (e.g. Lot 14 included 15 F-35As for Australia at the same ~$79M unit flyaway price as U.S. jets that year). Any difference in headline costs comes from currency exchange rates and what support/training is bundled in their budget. As of late 2023, Australia had received over 60 of its jets and is on track to have all 72 delivered by 2024; future consideration of additional F-35s will weigh their high through-life costs.

Other Buyers (Europe and Beyond): Numerous other allied nations are acquiring F-35As (and a few F-35Bs). The Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Italy, Canada and others that joined as partners effectively pay the same base price as the U.S., proportional to the variant they buy. They also contributed to development (in return for industrial workshare). Some partners have noted that early low-rate production jets cost more; for example, Italy’s first few F-35A/B jets were quite expensive and Italy built its own FACO in Cameri which added cost. But as the production stabilized, their later jets are close to the going rate. Non-partner customers like South Korea, Poland, Belgium, Finland, Switzerland, etc. are FMS cases – they generally sign large contracts that include not just the aircraft but simulators, engines, spare parts, and years of support. For example, Poland’s 32 F-35A deal in 2020 was $4.6 billion including a training and logistics package, which is about $144M per jet all-in. But the Polish Defense Ministry clarified the flyaway cost of the jet itself in that deal was around $87M, with the rest being support and initial sustainment costs. Finland’s 2021 order for 64 F-35As was about €8.4 billion (~$9.4B), which includes weapons and support through 2030 – again averaging ~$147M per jet with everything included, while the airframes alone would be much less.

In summary, allied nations typically pay roughly $80–$110M for each F-35 airframe (depending on variant and lot), which is comparable to U.S. prices. But total contract values for international purchases are much higher on a per-jet basis because they bundle in weapons, simulators, upgrades, spare parts, and maintenance support upfront. There aren’t exactly “discounts” for allies beyond the price reduction everyone enjoys from the economies of a large joint production run. However, partner nations avoid the FMS surcharge and had some influence in development, whereas late-coming buyers pay the FMS fee and sometimes face additional costs to integrate the F-35 into their local infrastructure. Notably, the F-35 program structure means no country pays a dramatically different base price for the jet itself – a British F-35B or a Japanese F-35A costs about what a U.S. one does off the production line. The differences are in added content: e.g. Japan paying extra for domestic assembly, or others paying for bespoke requirements and support. The U.S. has also occasionally used its clout to negotiate better deals for all; for instance, a multi-year “block buy” for Lots 12–14 drove prices down for every customer involved.

Conclusion

Determining “how much one F-35 really costs” depends on what costs are counted. In pure production terms, a single F-35A today costs on the order of $80 million, with the B and C variants around $100 million or slightly above. These unit costs have come down significantly from the program’s early years, thanks to higher production rates and efficiency gains. But the F-35’s true expense must include its lifelong support: fuel, maintenance, parts, upgrades, and personnel. When those are factored in, the cost of owning and operating one F-35 over decades can reach several hundred million dollars per jet, and the U.S. is staring at sustainment bills exceeding $1.5 trillion for the planned fleet. Allies face the same reality on a proportional scale.

International buyers pay roughly the same for the aircraft itself, but total program expenditures vary based on support packages and national choices (like local assembly or unique weapons integration). For example, the U.K. pays about $115M for an F-35B flyaway, similar to the U.S., while Japan’s all-in cost per F-35 (with support) appears higher (~$120M+) due to FMS fees and domestic assembly. In all cases, buying the F-35 is a major investment – one that nations justify by the jet’s advanced capabilities and multi-role flexibility.

As of 2025, the F-35 program has over 1,000 aircraft delivered worldwide and continues to grow. Ongoing efforts aim to control costs: the Pentagon is pressuring contractors to reduce sustainment expenses, and upgrades like the upcoming Block 4 software/hardware refresh are planned to be folded into future production without dramatically spiking unit prices. Still, observers note that the F-35 is “costing more and doing less” than envisioned, due to reliability shortfalls that limit availability. Keeping the F-35 affordable enough to field in the numbers required (while also developing next-generation systems) is a balancing act for defense planners.

In conclusion, an F-35’s “price tag” spans a spectrum: roughly $80–$110 million to procure one (depending on variant and lot), and on the order of $300–$400+ million to own and operate it over its lifetime. Allies buying the jet face similar unit costs, with differences mostly in added support. The F-35 Lightning II delivers unprecedented capability, but at a very steep cost – one that defense departments must budget for not just in the year of purchase, but every year thereafter.